WASTEWATER WOES

EDIE ZUVANICH Special to the Press

Editor’s note: This is the first in a three-part series examining the critical role of managing and controlling wastewater in Central Texas.

As Central Texas bursts at the seams with a population boom, many housing developers have found it easier and more affordable to build residential subdivisions outside of city limits, where they can avoid municipal codes and forego some of the expenses of city infrastructure and impact fees.

“When the state Legislature made it so that landowners could opt out of cities’ extraterritorial jurisdictions, and in the prior session, removed the cities’ ability to involuntarily annex property, it spurred city-like growth outside of cities,” said Williamson County Precinct 4 Commissioner Russ Boles. “The biggest city in Williamson County is now Williamson County.”

Boles said an unintended consequence of large residential development and municipal utility districts forming outside of city limits is the lack of infrastructure for wastewater, which has resulted in an unprecedented number of wastewater-discharge permit applications submitted to the Texas Commission on Environmental Quality.

At the end of August, TCEQ had five applications pending for new private wastewater treatment plants, or WWTPs, in the Taylor ETJ, two in Thrall’s ETJ and three bordering Hutto.

These permits allow a developer to build what is known as a package plant to collect household sewage, apply some level of treatment and then dump the wastewater into local ditches, streams and creeks, where it eventually makes its way to larger bodies of water such as the Brazos River.

Property owners, city councils and school districts have fought against having package plants discharging wastewater into creeks and open ditches that run through existing neighborhoods and past schools. Just outside Taylor, a group of neighbors are reaching out to everyone they can think of to support them against TCEQ approving a permit they say will affect their businesses and homes.

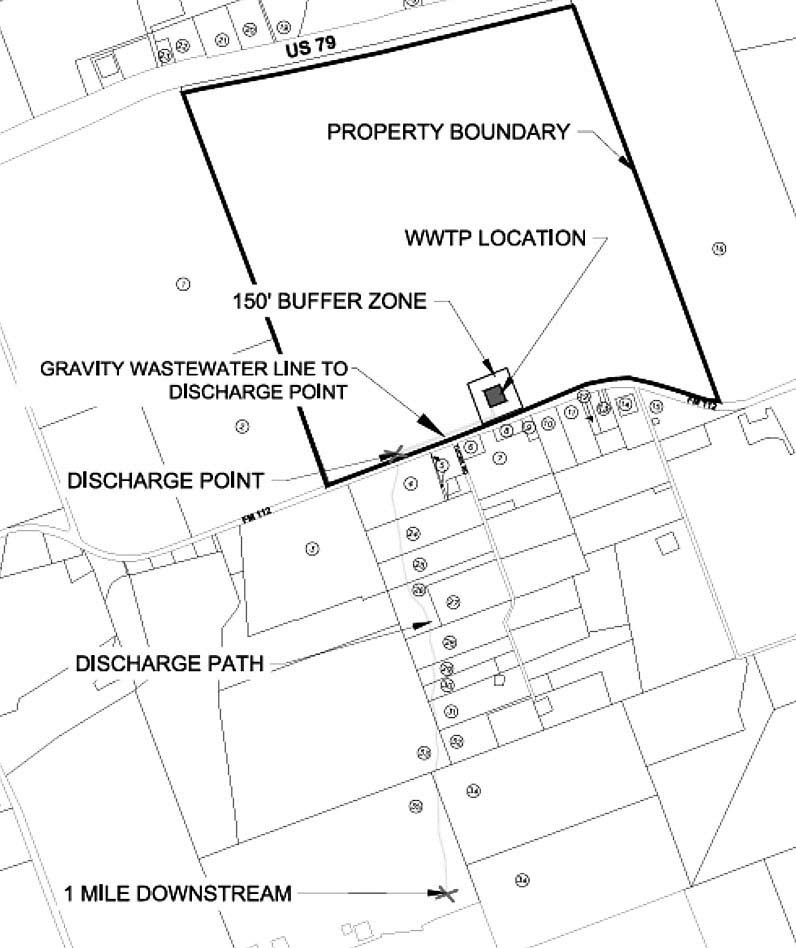

The permit is for a package plant that will support 612 new residences planned for a 487-acre site between U.S. 79 and FM 112. The plant itself will be northeast of and not far from 112 at Tucek Road. The development, owned by NMCV Taylor Property Investors LLC, will discharge up to 150,000 gallons of wastewater each day into a small, unnamed stream that travels one mile before meeting with Malish Lake. After three miles, the flowing effluent meets Mustang Creek which later joins with Brushy Creek.

“Discharges from the facility are expected to contain five-day carbonaceous biochemical oxygen demand (CBOD5), total suspended solids (TSS), ammonia nitrogen (NH3-N) and escherichia coli,” plus additional potential pollutants, according to the application.

Residents take action

Neighbors along this creek have submitted concerns to TCEQ about family gardens, businesses and livestock they fear could face a negative impact. Boles, state Sen. Charles Schwertner, state Rep. Caroline Harris Davila and Cyrus Reed, conservation director of the state chapter of the Sierra Club, have all written to TCEQ to ask for a contested hearing.

No hearing date has been set yet.

Engineers for the developer indicated they were unable to fully investigate what impact the wastewater discharge would have on nearby properties because downstream sites are privately owned and fenced.

Multiple voicemails and email messages to the developer’s representative Lauren Crone were unreturned. Crone is the Senior Project Manager at LJA Engineering, Inc. and is listed on the TCEQ application as the public point of contact for this project.

Neighbors say that within the first mile, as potential pollutants travel downstream, they will flow through 11 properties and could harm a rum distillery, food gardens, orchards, native wildlife, migratory birds, pets, livestock and cattle herds.

“We are concerned that the discharge parameters in the permit will fail to ensure that the receiving waters will not be harmful to people as the result of ingestion, consumption of aquatic organisms or contact with the skin by bacteria, pathogens or toxic constituents in the discharge. We are also concerned that the limitations in the permit fail to ensure that the receiving waters will not be toxic to terrestrial or aquatic wildlife due to chlorine levels or other constituents in the discharge,” Reed wrote in the Sierra Club’s hearing request to TCEQ.

Neighbors’ concerns Luis and Margaret Ayala own the property right across from the proposed plant, and theirs would be the first parcel the waste stream crossed.

“We have a great economic and health interest at risk. All aspects of our activities at this location — residential, commercial and agricultural — would be at peril,” Luis Ayala said. “We use water from the pond on our property for irrigating our land, but having that water contaminated with E. coli and other bacteria would pose a health hazard to our family, as simple foot traffic to our yard would risk infection and the introduction of the hazardous microorganisms into our living quarters.”

The Ayalas distill rum in a food-grade facility on the land and also operate The Rum University, a school that teaches professionals from around the world about the production of rum. They say having E. coli, other bacteria and toxins in the air or soil from an overflow would be enough to contaminate food-grade, indoor surfaces and affect fermentation. In addition, they are concerned any odor from a sewage flow would affect their ability to hold classes.

Property owner Tiffany Price worries about the effect wastewater would have on her business as well.

“I have established organic orchards and an organic garden that provides food for several generations. I also use the plants in my business, Places To Grow, as donations to those living in public housing to help them start patio gardens and community gardens. Contaminating this food source with wastewater discharge containing E. coli, pharmaceuticals and household chemicals is not acceptable,” Price wrote in her contested case request to TCEQ.

Glen Harrington has lived in the area nearly eight years, since he retired. He says he grows a garden, has fruit trees and chickens — all dependent on the unnamed stream.

“Our real objective is to grow what we eat as much as we can and give the rest away to family, friends and folks that have needs,” Harrington said.

Like other property owners, Harrington maintains the stream as it crosses his land, removing debris and shoring up erosion.

“When it’s 100 gallons a minute nonstop from now on, when do we ever get in there and fix the fences or the creek? Nobody seems to care that may cause a chain reaction to us. At what cost to your health do you want to get into the flowing current with who knows what’s in there?” Harrington asked.

Ayala said the impact to his business from the wastewater treatment plant could force him to relocate, but having the WWTP nearby would also cause a loss of property value in addition to the loss of business and the cost of building a new distillery.

“We are all going to lose value,” he said. “The American dream of owning a home or land or a business is having something that has intrinsic appreciation in value. The (WWTP) is going to chop the legs off of that.”

“ We have a great economic and health interest at risk. All aspects of our activities at this location — residential, commercial and agricultural — would be at peril.”

- Luis Ayala, property owner near the proposed wastewater plant