By all accounts, the Taylor Cemetery has needed some tender loving care for years. A high percentage of the headstones, some of which are more than 100 years old, need leveling at the municipally owned facility. Mowing the hilly 114acre cemetery, and cutting weeds around more than 10,000 headstones, is always a challenge.

However, after years of inconsistent enforcement of regulations that have been on the books since 2002, the city is making a slow but determined effort this year to remove most memorials, including all crosses, solar lights, vases, statues, stones and other tokens placed by mourners on and around gravestones.

“We understand that the gravesites in the Taylor Cemetery are an important place for people to remember their loved ones, and that the items they place on the graves are important mementos,” said Public Works Director Jim Gray in a prepared release. “Because this is a public cemetery that is available for all Taylor residents, it is important that it be kept as tidy and neat as possible, which is why the rules and regulations were written long ago.”

Taylor’s spokeswoman Stacey Osborne said she recognized it may not be easy for people to notice the fine print during their time of mourning, but that the families do receive the information beforehand through the funeral homes when they buy the plot. In addition, she said updates about the rules and regulations and the stricter enforcement have been posted on the city’s website and at the cemetery office.

The removal effort, which began in January, is being done on a section-by-section basis. Under the rules, only a small bouquet of flowers and a U.S. flag are permitted on or around the graves. Any other effects are tagged with a violation letter, which is also mailed to plot owners if the address is available.

The notice gives recipients 30 days for removal. Afterwards, cemetery staff remove the item and hold it for an additional 30 days before discarding it.

“It’s a timely and very work-heavy process to get everything done,” said District 1 Councilman Gerald Anderson. “We are doing our best to, No. 1, make sure that everybody is treated respectfully because it’s a sensitive subject, and, No. 2, that everyone is treated exactly the same and there is no favoritism of how lots are being chosen, cleaned up or removed.”

But to some family members, the city’s approach has been too heavy-handed, and even cruel.

“I don’t think they thought this through,” said Janie Morris, who takes care of her parents’ graves at the cemetery. “I 110% agree with (city staff) that they need to be taken care of, and not by them, but by family. If there’s a tattered flag, that needs to be taken down ... If people have put up an artificial flower that has changed colors, that needs to go. But, if a grave is neatly done, and it may have sentimental stuff on it, it needs to be left alone.”

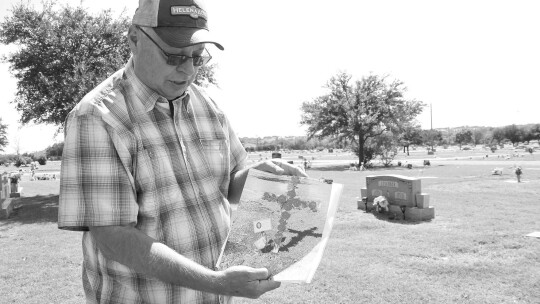

Felix Pavlicek said he and his wife have received several violation letters over the flower-filled, wooden crosses he made during the pandemic for the gravesites of many loved ones.

“I didn’t like the fact that I got a violation letter ... I have never gotten a violation in my life, and especially over a cross,” Pavlicek said. “I thought it would have been nicer if they had just said this is a friendly reminder that we are going to start implementing these different things and we want this done, this done and this done. I asked the sexton, ‘Are you going to fine us if we don’t cooperate?’” A sexton is a synonym for the manager of the cemetery. In addition, Pavlicek said he found it troubling crosses are no longer allowed in the cemetery. “The cross is a common symbol in Christianity for the resurrection and the promise of eternal life,” he said. “If you are not a Christian, maybe it doesn’t make a difference to you, but it does

to us.” Pavlicek’s sister-inlaw, Louanna Werchan Miller, who lives in Illinois, said she too was caught off-guard by the policy when their close family friend, Denise Richter, died unexpectedly earlier this year.

Because she was unable to attend the service, Werchan Miller had a large cross with fresh flowers delivered and placed on Richter’s grave. Less than a week later, Werchan Miller said she was told by city staff that her $200 arrangement had been thrown in the dumpster, despite being assured earlier that it would remain there for seven days after the funeral.

“There was really no good explanation,” Werchan Miller recalled. “He was really like, ‘Oh, we were cleaning, and we picked it up.’” Werchan Miller, a licensed clinical therapist in Texas and Illinois, said this decision compounded the grief she was already dealing with. “I have worked with grief and loss for 31 years, so this kind of touches me maybe differently than some, but when a loss is sudden and unexpected … it’s considered a traumatic loss,” Werchan Miller said. “The last thing that people need when they are grieving is unnecessary stress and additional hardships. So, I guess the other part of that I would say is there really has been no compassion or empathy shown.”

In addition, Richter’s niece, Molly King, who lives in Minnesota, said she felt sad that her aunt’s grave, which does not yet have a headstone, and had a small Texas A&M University flag and Pavlicek’s floral cross removed, has almost nothing there now to mark her gravesite.

“To know that it was taken away and she has got no mementos on her grave that will be placed there, it’s kind of heartbreaking,” King said. “And for other families, we saw so many other graves with drawings that little kids made, and little rocks and flowers left. To know that they were taken away seems cruel.”

Leslie Hill, a former funeral director who has relatives buried in the cemetery, said she thinks the cleanup has improved the site’s appearance, but thinks the city’s communication with families has been lacking. “It was horrible the way it looked; it looks better now,” Hill said. “I just feel like they should have told the people why.” For his part, Anderson said he understands how much these gravesites mean to families.

“I have my loved ones buried in the cemetery, and some relatives from the 1800s, and the early 1900s,” he said. “It was a segregated cemetery.

Blacks and Hispanics could only buy parcels in certain areas. It’s a subject that brings emotion outside, and when you start talking about messing with people’s gravesites, it gets even stickier.”

However, Anderson said he believes city staff is doing their best to navigate a difficult situation.

“I understand that it’s your loved ones, and you are trying to do your best to respect them, but as a city, we have to make those tough decisions of what is best for the cemetery as a whole,” Anderson said. “It’s almost impossible for our staff to be able to cut around a lot of these things because there is just so much stuff.”

Nevertheless, Anderson said going forward, he hopes communication with families can improve.

“The city as a whole wants to make sure that everybody is being respected,” Anderson said, “and if anybody feels like they were treated roughly, we apologize because that definitely was not our intention.”